|

| sent from: London, UK. destination: Hollywood, California, USA |

“If atmospheric turbulence is the reason why stars appear to twinkle, why wouldn’t planets also twinkle?”

I was challenging Maria after we strayed into a debate about planets supposedly not twinkling. It was an old argument between me and my father, one in which I had dug in my entire body not just my heels, too deeply to climb out. After all, was I not the amateur astronomer, the learned Space Scientist, no less? This time we could consult the ultimate repository of knowledge that we could not 20 years ago – the internet. Sure enough, the consensus was that planets did not twinkle (except in cases of v. high atmospheric turbulence), but the reasons why not made little sense until I came across an explanation that put it in more familiar terms.

It is a visual aliasing problem – a point of light being disturbed and trying to resolve onto a plane of finite resolution (the eye), vs a disk of light.

It is hard to concede something I’ve held onto for so long, especially when the evidence of my eyes has told me differently my whole life, hours gazing in to the Spanish night sky. Or did I bend reality to suit my notion of how I needed it to be?

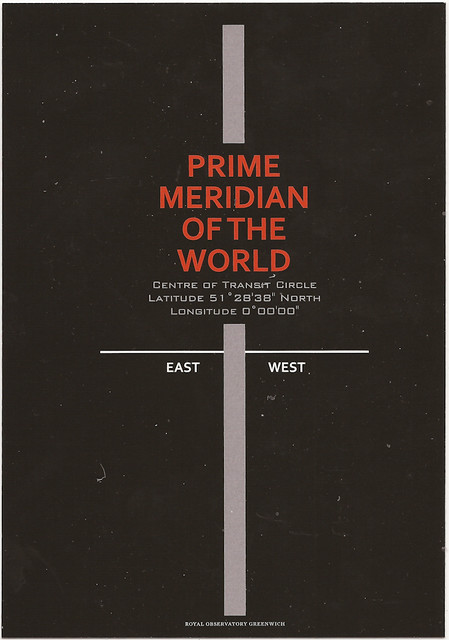

Last Saturday we visited the Greenwich Observatory for the first time, one of the places where England clings onto the remnants of its once dominance of the world. They had an excellent exhibition about the history of the calculation of longitude, which left enough questions unanswered to lead to lots of post-exhibition dinner argument about how they must have calculated this or that measurement with ancient instruments. It went from this onto other controversial topics, namely twinkle, twinkle little star.