Perhaps it was going to an all-boys’ school. Perhaps it was going to an all-boys’ school in England, but I had not heard of Anne Frank and her diary until I moved to the USA in my 20s, where it seemed to be a part of every school-child’s education.

So it was I walked in to Anne Frank’s house in Amsterdam, a novice, unfamiliar and unprepared. This is the very same house where she and her family hid for two years in a few small rooms concealed behind a bookcase, and where she wrote much of her diary.

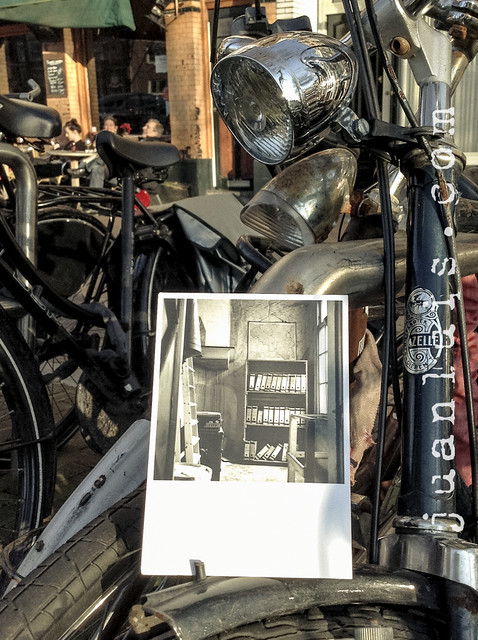

That very bookcase is still there, and stepping behind it you go into a kind of anti-Narnia, not something magical but something very mundane; small rooms with blacked out windows and preserved wallpaper with her girlish tokens to film stars pasted to the walls as any teenager would have.

The real power of Anne Frank is not so much in the specifics of her story, nor in the accumulation of photos, letters, stories. Neither is it in the painful recollections of her father who endured a life after that of his family’s, but in the realisation that her story is just one of many thousands, many millions like it; men, women, boys, girls – hiding, fearful, discovered, lost.